| Actor: Nina Hoss Director: Christian Petzold Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama, Mystery & Suspense Sub-Genres: Indie & Art House, Love & Romance, Mystery & Suspense Studio: Cinema Guild Format: DVD - Color,Widescreen,Anamorphic DVD Release Date: 03/31/2009 Original Release Date: 01/01/2009 Theatrical Release Date: 01/01/2009 Release Year: 2009 Run Time: 1hr 29min Screens: Color,Widescreen,Anamorphic Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 5 MPAA Rating: Unrated Languages: German See Also: |

Search - Yella on DVD

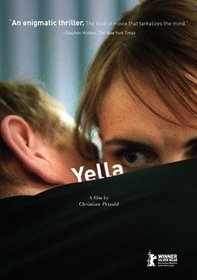

| Yella Actor: Nina Hoss Director: Christian Petzold Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama, Mystery & Suspense UR 2009 1hr 29min Narrowly escaping her volatile ex-husband, Yella flees her small hometown in former East Germany for a new life in the West. She finds a promising job with Philipp, a handsome business executive with whom an unlikely roman... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

|

Member Movie ReviewsReviewed on 8/13/2009... It’s clear that writer/director Christian Petzold is, at heart, a political filmmaker whose vision is imbued with the poetry and stylistic sensibilities of Germany’s grand cinematic history. Of late, German cinema has been making a strong resurgence with such films as The Lives of Others and The Counterfeiters. Germany’s comeback has much to do with political and social reform, but, unfortunately, my knowledge of the country’s socioeconomic and geopolitical structures is somewhat lacking. As such, I believe I may only be skimming the surface of what Yella has to offer. I’ll do my best to inform.

The film opens with Yella (Nina Hoss) traveling home to tell her father of the accounting job she plans to take in Hanover. She is interrupted by her soon-to-be-ex-husband, Ben (Hinnerk Schönemann), a ruined businessman who is desperate for Yella’s affection, forgiveness and perhaps even for some admission for her part in his ruination. It is clear that Ben is unstable, and he remains a haunting force throughout the film. The morning Yella is to leave, Ben shows up at her door, offering to drive her to the train station. Yella accepts. And . . . that’s as far as we can go. My first priority as a critic is not to my review, but to the film itself. Given that Yella’s narrative and mood depend on the viewer’s evolving perception of the film’s creeping, unfolding events, it would do the work a disservice to proceed any further. It would be incorrect to label Yella a thriller, though the film operates through similar mechanics. In fact, watching the film, I was strongly reminded of Michael Haneke’s masterfully unnerving Caché, which also operates within more than one genre. Again citing my lack of education concerning the current German climate, it’s clear that the film has a complex undercurrent of social and political examination. Yella’s desires act as the film’s axis point; it moves as she moves and changes as she becomes more aware of her actions and her aforementioned desires. She, through scenes of fascinating silence, cross-examines herself. These scenes are made palpable by Nina Hoss’ mesmerizing performance. As Yella, Hoss speaks very little. Her performance is all nuance and fine minutia. She communicates the bulk of her character’s psychology through her quiet observations: the way she sits; the way she looks at a stranger via her periphery; the way her eyes travel a room during venture capital meetings; the way she builds to an inevitable cry. It’s an extraordinary performance. Petzold frames Hoss’ performance with a subdued visual style, often repeating certain angles to emphasize the film’s dreamy and mysterious mise-en-scène. The film is almost entirely realized through contrasts, repetition and strange, eerie episodes that exist to upset our perception. I would say that the film is made for satisfying consumption—and a fine meal it is—but not necessarily complete comprehension. You’ll find nothing concrete, only ideas that emerge and then disappear in the fog. With that in mind, and considering what I think Petzold’s ultimate intentions were, I found the film’s ending somewhat bothersome. Like the rest of the film, Yella’s fate is open to interpretation, but I felt the film existed in a more heightened intellectual sense without Petzold’s final reveal. Though, this is really a minor quibble for what is an excellent and highly stimulating film. Movie ReviewsA triumph for modern day German cinema Christopher Langford | Florida | 06/20/2009 (4 out of 5 stars) "This enigmatic drama is a story of a young woman who confronts her ambitions and insecurities head on. The film starts with Yella accepting a new job and moving to the more modernized western part of the country. With hopes for a better future, the life she leaves behind include her loving father, her obsessive husband, and the stability of a reality understood.

Christian Petzold uses a bold no frills approach to exhibit this thought provoking film. The narrative has a minimalistic quality which serves the film well, allowing the viewer to focus on the subtle yet compelling performance by actress Nina Hoss. Yella is an intelligently layered film and a triumph for modern day German cinema. " |