| Actors: William J. Eggleston, Michael Almereyda, Winston Eggleston, Leigh Haizlip Director: Michael Almereyda Creators: Michael Almereyda, Johannes Weuthen, Joshua Falcon, Karen Choy, Alexis Zoullas, Anthony Katagas, Donald Rosenfeld, Heather Parks, James Patterson, Jesse Dylan Genres: Educational, Documentary Sub-Genres: Educational, Documentary Studio: Palm Pictures / Umvd Format: DVD - Color,Full Screen DVD Release Date: 02/14/2006 Release Year: 2006 Run Time: 1hr 27min Screens: Color,Full Screen Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 2 MPAA Rating: NR (Not Rated) Languages: English |

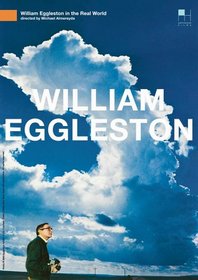

Search - William Eggleston In the Real World on DVD

| William Eggleston In the Real World Actors: William J. Eggleston, Michael Almereyda, Winston Eggleston, Leigh Haizlip Director: Michael Almereyda Genres: Educational, Documentary NR 2006 1hr 27min In 1976, William Eggleston?s hallucinatory, Faulknerian images were featured in the Museum of Modern Art?s first one-man exhibition of color photographs. It is rare for an artist of such stature to allow himself to be sho... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

|

Movie ReviewsNot great, but not that bad Mediahound | SF Bay Area, CA United States | 03/16/2006 (3 out of 5 stars) "Given the source material I would have edited this project much differently. There are a lot of shots where Eggleston is just sitting there doing nothing but thinking, or walking around the streets not really photographing. The viewer gleens surprisingly little into Eggleston's photographic techniques or motivations. We do gleen a bit into his psyche and demons (substance abuse) through interviews with Eggleston and his friends, and narration by the filmmaker. As a professional photographer, I learned something about what makes Eggleston tick, but probably only as much as he wanted me to learn, certainly more so than I would have without watching this DVD. So, this DVD is not completely worthless but it reallly could have been a lot better. You do get to see many of William Eggleston's photos not just in the main show but also a few (not an abundance though) in the extras on the DVD." Eccentric Pleasures William H. Boling Jr. | Atlanta, GA U | 08/27/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "I am very biased in favor of anything that would bring the extraordinary work of Mr. Eggleston to a wider audience - still please trust me when I say that this film is a remarkable acheivement and a riveting experience and would be even if I knew nothing of Mr. Eggleston's art. Mr. Almereyda has tricked the ultimate trickster into revealing more of himself than one might have thought possible. Not since Duchamp has anyone delivered the artistic goods with correspondingly well targeted mockery of the 'received wisdoms' of art and photography as Mr. Eggleston. He is a master of misdirection and inscrutible yet unfailingly potent verbal and visual renderings. So when I heard that someone had set out to produce a documentary on the subject it was a little like hearing that I should step outside if I wanted to watch a neighbor catch a greased pig. I wasn't expecting we would be enjoying pork chops for dinner but I knew there would be quite a show. Mr. Almereyda's film delivers the show and the bacon. First, the show - Mr. Eggleston's eccentric and loving world of family and friends are photogenic and interesting. They are presented as they are without much fuss and caught in media res. We begin the film by simply ambling along with Mr. Eggleston and his son Winston as they trip over pictures that suggest and offer themselves to Mr. Eggleston, falling as it were into the campfire of his vision like so many moths from the real world looking for that something more. By following this work in the field we get to see and know the craftsman in his primary state -- someone who is out in the world looking and searching still. This allows us more ease as we move into other aspects of his family life and career. This early field work set up helps especially when we're presented with his dialogues which Mr. Eggleston intends (as with the statements of Jasper Johns, Duchamp or some Zen master) to enlighten through confusion and the confounding of the irrational nature of "the real world". Second, the bacon -- where Mr. Almereyda's work acheives its greatest insight is in revealing Mr. Eggleston's complex yet fundamentally loving nature. A man who despite a well groomed and tended reputation as an enfant terrible is tender to and with all those we see encountered from the very close -- his wife, son, and close friends to the most casual encounters. Witness his thoughtful reassurance to the shopkeeper who offers to move the pinata he wants to photograph -- in reassuring tones he congratulates her on how she's positioned the thing -- he says she's got it just right. Ultimately, I think that is the bacon -- Mr. Egglston is revealed as a great lover of the world and all that's in it -- even with all the suffering and strife and odd-ball visual awkwardness he sees and presents to us a world that whether we recognize it or not "is just right"." Illuminating S. Jacobs | New England | 05/12/2006 (4 out of 5 stars) "I first saw a pre-release, rough draft version of the film at the Harvard Film Archives in 2004. I thought it was an illuminating and intimate view into the life of an important American artist. I feel the scenes in which Eggleston is walking and looking, as well as his partiality for liquor and the various high and low social realms he comfortably navigates are essential: they give the audience of this documentary a unique insight into the plausible mechanics that make Eggleston, and his imagery, what they are." I wanted to like it, but alas... Ronald Cowie | Las Vegas, Nevada | 06/17/2007 (2 out of 5 stars) "I bought this to show my class and found it both a little boring and sad. Yes, Eggleston is a national treasure but he also is a train wreck.

The documentary is not very revealing and what it reveals really isn't that interesting. I got through this once but haven't watched it again. I like looking at his work but really didn't learn anything from this." |