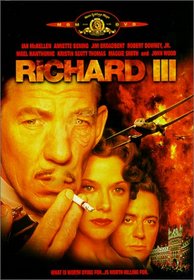

| Actors: Ian McKellen, Annette Bening, Jim Broadbent, Robert Downey Jr., Nigel Hawthorne Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama, Mystery & Suspense Sub-Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama, Mystery & Suspense Studio: MGM (Video & DVD) Format: DVD - Color,Full Screen,Widescreen,Letterboxed - Closed-captioned DVD Release Date: 03/28/2000 Original Release Date: 12/29/1995 Theatrical Release Date: 12/29/1995 Release Year: 2000 Run Time: 1hr 44min Screens: Color,Full Screen,Widescreen,Letterboxed Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 0 MPAA Rating: R (Restricted) Languages: English Subtitles: Spanish, French |

Search - Richard III on DVD

| Richard III Actors: Ian McKellen, Annette Bening, Jim Broadbent, Robert Downey Jr., Nigel Hawthorne Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama, Mystery & Suspense R 2000 1hr 44min Shakespeare's immortal tale of ambition, lust and murderous treachery is brilliantly updated and brought to life in this riveting, 20th-century masterpiece. Boasting breathtaking performances, unforgettable imagery and two... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

Similarly Requested DVDs

|

Member Movie ReviewsReviewed on 5/17/2011... My husband understands Shakespeare, while I do not. What I found interesting, though, is how the movie makers managed to use the actual words from the play, yet set it in a much more modern (WW II) time and place. 2 of 2 member(s) found this review helpful.

Movie ReviewsVillany Unveiled. Themis-Athena | from somewhere between California and Germany | 05/29/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "A gala ball: The York family celebrate their reascent to power; the War of Roses (named for the feuding houses' heraldic badges: Lancaster's red and York's white rose) is almost over. Actually, the year is 1471, but for present purposes, we're in the 1930s. A singer delivers a swinging "Come live with me and be my love." Richard of Gloucester (Sir Ian McKellen), the reinstated sickly King Edward IV's (John Wood's) youngest brother, moves through the crowd; observing, watching his second brother George, Duke of Clarence (Nigel Hawthorne) being quietly led off by Tower warden Brackenbury (Donald Sumpter) and his subalterns. With Clarence gone, Richard seizes the microphone, its discordant screech cutting through the singer's applause, and he, who himself made this night possible by killing King Henry VI of Lancaster and his son at Tewkesbury, begins a victory speech: "Now is the winter of our discontent made glorious summer by this sun of York" (cut to Edward, who regally acknowledges the tribute). But when Richard mentions "grim-visaged war," who "smooth'd his wrinkled front," the camera closes in on his mouth, turning it into a grimace reminiscent of the legend known to any spectator in Shakespeare's Globe Theatre: that he wasn't just born "with his feet first" but also "with teeth in his mouth;" hence, not only crippled (though whether also hunchbacked is uncertain) but cursed from birth, his physical deformity merely outwardly representing his inner evil. Then, mid-sentence, the image cuts again. Richard enters a bathroom; and as he continues his monologue we see that only now, relieving himself and talking - with narcissistic pleasure - to his own image in the mirror, he truly speaks his mind; contemptuously dismissing a war that's lost its menace and "capers nimbly in a lady's bedchamber," and determining that, since he now has no delight but to mock his own deformed shadow, and "cannot prove a lover," he'll "prove a villain and hate the idle pleasures of these days." Thus, Richard's first soliloquy, which actually opens the play on a London street, brilliantly demonstrates the signature elements of this movie's (and the preceding stage production's) success: not only its updated 20th century context but its creative use of settings and imagery; boldly cutting and rearranging Shakespeare's words without anytime, however, betraying his intent. Indeed, that pattern is already set with the prologue's murder of King Henry VI and his son, where following a telegraph report that "Richard of Gloucester is at hand - he holds his course toward Tewkesbury" (slightly altered lines from the preceding "King Henry VI"'s last scenes) Richard himself emerges from a tank breaking through the royal headquarters' wall, breathing heavily through a gas mask: As his shots ring out, riddling the prince with bullets, the blood-red letters R-I-C-H-A-R-D-III appear across the screen. And as creatively it continues: Richard woos Lady Anne (Kristin Scott Thomas), Henry's daughter-in-law, in a morgue instead of a street (near her husband's casket), and later drives her into drug abuse. Henry's Cassandra-like widow Margaret is one of several characters omitted entirely; whereas foreign-born Queen Elizabeth is purposely cast with an American (Annette Benning), whose performance has equally purposeful overtones of Wallis Simpson; and whose playboy-brother Earl Rivers (Robert Downey Jr.) dies "in the act." Clarence is murdered while the rest of the family sits down to a lavish (although discordant) dinner. When upon Richard's ally Lord Buckingham's (Jim Broadbent's) machinations, he is "persuaded" to take the crown, he emerges from a veritable film star's dressing room complete with full-sized mirror and manicurists (sold to the attending crowd outside as "two deep divines" praying with him). Tyrrell (Adrian Dunbar), already one of Clarence's murderers, quickly rises through uniformed ranks as he further bloodies his hands. Richard's and Elizabeth's final spar over her daughter's hand takes place in the train-wagon serving as his field headquarters; and we actually see that same princess wed to his arch-enemy Richmond (Dominic West), King Henry VII-to-be and founder of the Tudor dynasty, with lines taken from Richmond's closing monologue. Perhaps most importantly, we also witness Richard's coronation, which Shakespeare himself - honoring that ceremony's perception as holy - decided not to show; although even here it is presented not as a glorious procedure of state but only in a brief snippet rerun immediately from the distance of a private, black-and-white film shown only for Richard's and his entourage's benefit. And challenging as this project is, its stellar cast - also including Maggie Smith (a formidable Duchess of York), Jim Carter (Prime Minister Lord Hastings), Roger Hammond (the Archbishop), and Tim McInnerny and Bill Paterson (Richard's underlings Catesby and Ratcliffe) - uniformly prove themselves more than up to the task. Even if the temporal setting didn't already spell out the allegory on the universality of evil that McKellen and director Richard Loncraine obviously intend, you'd have to be blind to miss the visual references to fascism: the uniforms, the gathering modeled on the infamous Nuremberg Reichsparteitag, the long red banners with a black boar in a white circle (playing up the image of the boar Shakespeare himself uses: similarly, Richard's and Tyrrell's first meeting is set in a pig-sty, and Lord Stanley's [Edward Hardwicke's] prophetic dream follows an incident where Richard, for a split-second, loses his self-control). But the imagery goes even further: Richard's narcissism is reminiscent of Chaplin's "Great Dictator;" and you don't have to watch this movie contemporaneously with the latest "Star Wars" installment to visualize Darth Vader during his gas mask-endowed entry in the first scene. "[T]hus I clothe my naked villany with odd old ends stol'n out of holy writ; and seem a saint when most I play the devil," Richard comments in the play: if there's one line I regret to see cut it's the one so clearly encompassing the way many a modern despot assumes power, too; by cloaking his true intent in the veneer of formal legality. Even so: this is a highlight among the recent Shakespeare adaptations; under no circumstances to be missed. Also recommended: The Oxford Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition Olivier's Shakespeare - Criterion Collection (Hamlet / Henry V / Richard III) BBC Shakespeare Histories (Henry IV Parts 1 and 2, Henry V, Richard II, Richard III) DVD Giftbox BBC Shakespeare Tragedies DVD Giftbox Henry V William Shakespeare's Hamlet (Two-Disc Special Edition) Grigori Kozintsev's Hamlet Hamlet Peter Brook's King Lear Julius Caesar" To fully enjoy this version you first have to know the play Lawrance M. Bernabo | The Zenith City, Duluth, Minnesota | 09/28/2000 (4 out of 5 stars) "Every since Orson Welles and John Houseman started the trend of updating Shakespeare, there have been several innovative interpretations of the Bard. More so that the drug lord culture of 1996's "William Shakespeare's Romeo & Juliet," this 1995 version of "Richard III" cast in Edwardian England is a successful addition to the tradition. Of course it has one big advantage over other such films in that it is based on the captivating stage production by Ian McKellen and Richard Eyre. Certainly McKellen is totally comfortable in his role, adding a 20th century venire of evil to the calculating Duke of Gloucster on his way to the crown. This Richard is readily accessible to a contemporary audience.But there is one extremely important caveat to enjoying this film: you have to be familiar with the original play, otherwise you will totally lose the irony of the alterations. For example, in the play Richard woos his intended bride as she follows the casket containing her husband, who had been slain by Richard, who at one point ponders whether a woman had ever been wooed let alone won in such a manner. In the film version the scene takes place in a morgue, with the dead husband lying on the gurney. The scene is gruesome, something you would expect in a splatter flick rather than Shakespeare, but has a certain validity given the original scene. It is, after all, just a question of setting. But if you are not well versed in "Richard III," you simply can not appreciate the McKellen version. Of course, this is a marvelous opportunity for teachers who can screen the film, or key scenes, after students have read the play. Imagine the discussions you can have on the range and validity of interpretation available. You can do the same sort of thing with "MacBeth"/"Throne of Blood," "King Lear"/"Ran," or the Olivier/Branagh versions of "Henry V." Or you can just enjoy this film at home and mull over such wonders on your own." A brilliant and imaginative interpretation C. Colt | San Francisco, CA United States | 05/25/2000 (5 out of 5 stars) "Ian McKellen's "Richard III" is a brilliant 20th Century adaptation of the Shakespeare original. McKellen sets the murderous intrigue and civil strife of the play in an imaginary fascist period of English History. In doing this, he removes the story from its historical context and demonstrates the timeless nature of its themes. The original story was set during the War of the Roses, a bitter succession conflict which took place in pre-Tudor England. None of the medieval butchery is lost on us when we see it take place in a fascist context.The central theme of Richard III is not ambition or ruthlessness but the power of momentum. Richard relies on both physical and rhetorical momentum for his success. Physically, he must always be on the move. Once his movement is stopped he is doomed. Richard makes this abundantly clear in the play and in the film when his transportation is destroyed at the Battle of Bosworth field and he can no longer move. Richard says "a horse a horse,my kingdom for a horse" meaning that without movement he loses the battle and with it his life and his kingdom. This signature death speech is even a bit ironic in the film since it is Richard's jeep that is shot out from him which means that he is speaking metaphorically when he refers to it as a horse. What could be more fitting for a fascist leader?Momentum is also crucial to Richard's rhetoric. On two occasions in the play, Richard must convince a woman whose husband he has murdered to marry him. Richard accomplishes this the first time by matching each of the widow's arguments with a witty retort until she has none left. But Richard is later unable to do this with the second widow. He begins his confident stream of witty retorts but is flustered by and then outdone by her. Rhetorically he has lost his momentum and with it his power to dominate and control. Momentum is as crucial to modern despots as it was to the tyrants of Shakespeare's time. Hitler mesmerized a generation of Germans with speeches whose content made little sense but whose momentum carried the day. And like Richard III, Hitler was only successful as long as his army could keep on the move. I wonder if any Panzer driver stuck in the mud and snow of Stalingrad in 1942 found himself muttering "a horse a horse, my kindom for a horse"?"

|