| Actors: Esther Gorintin, Nino Khomasuridze, Dinara Drukarova, Temur Kalandadze, Rusudan Bolqvadze Director: Julie Bertuccelli Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama Sub-Genres: Indie & Art House, Family Life Studio: Zeitgeist Films Format: DVD - Color,Widescreen,Anamorphic - Subtitled DVD Release Date: 01/25/2005 Release Year: 2005 Run Time: 1hr 39min Screens: Color,Widescreen,Anamorphic Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 4 MPAA Rating: Unrated Languages: French, Georgian, Russian Subtitles: English |

Search - Since Otar Left on DVD

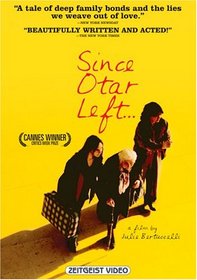

| Since Otar Left Actors: Esther Gorintin, Nino Khomasuridze, Dinara Drukarova, Temur Kalandadze, Rusudan Bolqvadze Director: Julie Bertuccelli Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama UR 2005 1hr 39min Julie Bertuccelli's acclaimed first feature is a charming, bittersweet tale of deception and affection. Three women--strong-willed Eka (90-year-old Esther Gorintin), her long-suffering daughter Marina and rebellious grandd... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

Similarly Requested DVDs

|

Movie Reviews"So what if we know about the lies?" "So what if we don't?" Grady Harp | Los Angeles, CA United States | 02/05/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "SINCE OTAR LEFT ("Depuis qu'Otar est parti...")is a wonderfully sensitive exploration about the transitions made from youth to middle age to old age and the associated means of communication that imprison us or free us at every juncture. Julie Bertucelli directs this tender tale co-written with Bernard Renucci that focuses on the lives of three women: Eka (in a brilliantly subdued portrayal by Esther Gorintin) who is the elderly mother to Marina (Nino Khomasuridze) and grandmother to Ada (Dinera Drukarova). The three live together in a por crowded apartmanet in Tbilisi, Georgia enduring private disappointments: Eka's life is flat line except for the weekly letters form her physician son Otar in Paris (he has escaped Georgia only to find poverty in the poor sector as a construction worker which he keeps as his secret); Marina feels 'second rate' to her mother's preferred son Otar in Paris and remains unmarried and discontent with her station in life, sleeping with one man Tengiz (Temur Kalandadze) knowing htat he may be good in bed but is not husband material; and Ada, who is young, high-spirited, and discontent with the rigidity of living in Tbilisi with all of its restrictions on her life. While Eka is away for a week at the family dacha, Marina and Ada receive news that Otar is dead by accidental circumstances. Knowing Eka will be devastated with the news of the loss of her 'favorite child', Marina decides to keep it a secret and Ada reluctantly goes along with the lie, consenting to continue writing letters from Otar to protect the feelings of the aging Eka - a lie that seems to be working fine when Eka returns. Marina and Ada leave for a week's trip, and return to find that Eka has decided to sell everything she owns in order to buy tickets to Paris for the three of the women to visit Otar. Marina and Ada maintain the lie, accompany Eka, and while off seeing the sites of Paris (a city Ada adores and feels renewed in) Eka sets out on her own to find Otar. She eventually finds the apartment where he lived and is brusquely informed by the tenant that Otar the doctor died some months back. Eka is stunned, but in her contemplation she copes with the reality, and decides not to share her newfound news with Marina and Ada. With enormous courage and simple humanity Eka tells Marina and Ada her own lie that Otar has left for America where he will be able to find freedom and success and happiness. The way this effects the three women is the poignant ending of the film. Each of the actors in this exquisite story is absolutely first rate. The photography is correctly claustrophobic in Tbilisi and open in Paris. The dialogue is both in French and Georgian and the subtitles are superb. This is a powerful story and a moving film that knocks on the doors of our hearts without the least hint of being saccharine. Highly Recommended. Grady Harp, February 2005" Poignant Cinematic Experience Through Three Generations... Kim Anehall | Chicago, IL USA | 03/30/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "After the fall of the Eastern Block the Soviet Union broke into several nations. One of these nations is Georgia, a small country on the eastern side of the Black Sea. Georgia, like so many other countries in the former Warsaw pact, was left to fend for itself, as this former group of nations crumbled in the aftermath of the United States' increase in military spending in the Cold War. Over a decade after the end of the Cold War Georgia is still struggling financially, as people still do not have reliable electricity, warm constant water, or fully operational phone lines. However, Since Otar Left is not about the Cold War, but it is essential to have an understanding of the history. This history provides an understanding of how Otar's family ended up in the situation in which they exist. Otar, a person the audience never gets to meet more than over phone conversations or in old photographs has left Georgia to pursue better luck outside the nation. To better explain his desperation one should tell that he no longer practices medicine in Georgia, as it is more fruitful for him to live in France and work illegally as a caretaker for an apartment complex while trying to find something better. Occasionally, Otar has saved up enough to send home a little money to his mother, Eka (Esther Gorintin), who is the story's true main character. Esther Gorintin was 85 when she made her debut in film by performing in Emmanuel Finkiel's film Voyages (1999), and she since been working in eight other films including Since Otar Left. Eka is a lovely old lady who still lives in the past, as she even goes as far to state that Stalin was a great man. Nonetheless, Eka is an adorable old lady that it is impossible to get angry with, as she means well in everything she does and says. She also misses her son, Otar, who writes and calls as often as he can spare time and afford. Eka's self-centered daughter, Marina (Nino Khomasuridze), seems to suffer from insecurities in regards to her brother's prestige and kindness, which she tries to down play at every chance she gets. Marina has a daughter, Ada (Dinara Drukarova), who dreams of something better while her mother's constant demands and guilt inducing moments seem to hold her back. It is almost as if Marina is co-dependent on her daughter in order for her to feel any kind of self-worth. The three women live together without any man in the house, as Marina lost her husband during the Afghani war and Ada has not found the appropriate man to bring her away from the misery in which she lives. One day sad news arrives to the home of the three women. Otar has died, and somehow Marina decides not to tell her mother. The psychodynamics of her background come into play and she finds a role in which she is stronger than before because she finds an opportunity to control the situation. Ada thinks it is cruel, but Marina is convincing and Ada does as her mother requests. Marina tells Ada fake letters and a she comes up with reasons why Otar has not tried to contact them. The whole scene is very sad, yet the social circumstances in which they live provides some reason of why to not bring the heartbreaking news to the grandmother. Since Otar Left is a wonderful film displaying the social dynamics of three women living in the shadow of the collapse of the Eastern Block. The hopes, dreams, and nostalgia are interconnected through three different generations, which is even conveyed in the story. The first time director Julie Bertucelli does marvelous job directing a film that reaches the audience's inner most feelings through a wide range of emotions. This is enhanced through terrific visuals of the Georgian town in which the three women live such as the post office, the street, and the home in which they live. The film's conclusion will provide a sense of hope that is torn between poignant sorrow and bliss leaving the audience deliberately with several notions to contemplate." Charming Drama about Three Women, White Lie and Consequences Tsuyoshi | Kyoto, Japan | 01/01/2005 (4 out of 5 stars) "'Since Otar Left' is a very tender, touching, and realistic drama about three women living in Tbilisi, the central city of Georgia that was once part of Soviet Union. (The film itself is produced by companies in France and Belgium, and the two of the principal actresses are not Georgian, though.) Eka is a grandmother living in the city, independent, a bit stubborn, but still a charming old lady living in today's Tbilisi. Her life is rather monotonous (except her slight arguments with her daughter Marina), but Eka still has her own pleasure -- occasional phone calls and letters from Otar, her kind son who has left the city for Paris. And Otar's letters are read by Eka's granddaughter Ada, who dreams of going to France, leaving the country behind. One day, something happens, which changes the established patterns of their life. While Eka is away from home, the daughter and granddaughter receives a phone call from Paris, which says, Otar is gone -- gone forever. The two women, at first devastated, decide to keep on pretending that words are still coming from Otar, faking letters, in order that their grandmom can be protected from the inevitable shock. Where these white lies will lead the three women, is not a new story -- we have recently seen a similar premise in 'Good Bye Lenin!' -- nor the humors and pathos the film provides (though they are well-balanced and often effective). The greatest things about the film is its characters, who are so real, so incively porrayed that you find someone you know in one or all of them. The first-time director Julie Bertuceli has an eye for characters and ordinary life, always deft at showing those apparently trivial things in life, which later turn out very important, and even precious. The three actresses are all perfect, but the most wonderful is Eka played by Esther Gorintin, who was 90 years old when the film was released. And more incredible thing is that she turned professional when she was 85. She is so natural and delightful that you will see some part of your own grandmoms in her. Just fantastic. If you like well-made drama with good characters, see this one. Though the story is not exceptional, and some parts suffer from slow pace and slightly detached approach, the film remains engaing, especially Eka, the grandmother." Surviving by living a fiction Jay Dickson | Portland, OR | 06/11/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "Life in Tbilisi in 2002 for the three generations of women at the center of this film--the indomitable 90-year old Eka, her cynical daughter Marina, and her dutiful teenage granddaughter Ada-- is not very easy. The electricity and the water in their formerly elegant apartment is intermittent, and the only sources of income are what little Marina can make by selling household objects in the city park and the money sent to them from Paris by Eka's beloved son Otar, who has left Georgia to eke out a better life. The film starts by letting us get caught up in the rhythms of these women's lives as they squabble, complain, tend to one another, and wait for Otar to contact his doting mother by phone of by letter--and then a disaster occurs when Marina and Ada discover that Otar has died while illegally working on a construction site. Fearful of devastating the physically fragile Eka, they concoct an elaborate lie that he is still alive and sending his mother letters Ada pens.

On its own terms, this little film--the first-time effort of Julie Bertocelli--is just about perfect. The characters are beautifully layered, so that our initial opinions of them become slowly changed as the film progresses so we see that Eka is much more generous, Marina more fragile, and Ada more independent than we initially are led to believe. The film is an extended meditation on nostalgia, and how we cling to our pasts to survive and expect our loved ones to do the same; it's also a study of beauty, and Bertocelli's lovely use of composition and color show us why living in Shevardnaze's slowly disintegrating Georgia after the fall of the USSR has its compensations. This is an excellent film--one that has a subject matter that will seem unfamiliar to many Western viewers who do not know Tbilisi or Georgia, but one that is both rich and repaying." |