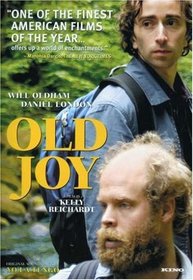

| Actors: Daniel London, Will Oldham, Tanya Smith, Robin Rosenberg, Keri Moran Director: Kelly Reichardt Creators: Kelly Reichardt, Anish Savjani, Jay Van Hoy, Joshua Blum, Julie Fischer, Lars Knudsen, Mike S. Ryan, Jonathan Raymond Genres: Drama Sub-Genres: Drama Studio: KINO INTERNATIONAL Format: DVD - Color,Widescreen - Closed-captioned DVD Release Date: 05/01/2007 Original Release Date: 01/01/2006 Theatrical Release Date: 01/01/2006 Release Year: 2007 Run Time: 1hr 16min Screens: Color,Widescreen Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 4 MPAA Rating: Unrated Languages: English |

Search - Old Joy on DVD

| Old Joy Actors: Daniel London, Will Oldham, Tanya Smith, Robin Rosenberg, Keri Moran Director: Kelly Reichardt Genres: Drama UR 2007 1hr 16min Studio: Kino International Release Date: 05/01/2007 Run time: 76 minutes |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

Similarly Requested DVDs

|

Movie Reviews"Superfluous Men" Stanley H. Nemeth | Garden Grove, CA United States | 07/08/2007 (4 out of 5 stars) "The political dimension of this unusual film hasn't, I think, been sufficiently emphasized. Both of the central figures, Kurt and Mark, are marginal men, recognizable leftover types from the past century, neither of whom has any citizen's presence much less clout in current America. Kurt holds on to a stale, hip sort of behavior which actually long antedates his own generation's, while Mark, his friend from several years back, is a former hipster, now turned yuppie, a fan of "Air America," married, in possession of a house and with a kid on the way. Mark is converting himself into a work-a-daddy, but he has intimations that something's missing in this recently chosen sort of life. At heart, he, like Kurt, is revealed as still just a boy-man. Accordingly, he jumps at the chance to escape from his house and pregnant wife to try to recapture past youthful good times with Kurt through a road trip to Bagby Hot Springs in the Cascade Mountains of Oregon. Mere location, as we'll see though, doesn't make much difference when it comes to fostering true human intimacy. One can be as alienated or happy in the beautiful countryside as in the industrial city. To emphasize this, the camera shows us exquisite birds on tree branches in the city and leftover garbage at an otherwise naturally beautiful country campsite. What these two guys discover on their trip is "the people gap," the awareness that there may be no greater strangers than old friends who've been apart for several years. Intellectually and emotionally, Kurt and Mark have nothing in common any longer; the theme of the film, accordingly, is that of the sadness of time, change, and inevitable loss. The photography, beautiful in its fleeting images of scenery, itself richly underscores this theme. On the road, the former friends pretty quickly see they actually have little to say to one another. Therefore, Kurt mostly fills time smoking pot, while Mark talks too frequently on his cellphone. Although both men sense the gap between them, the less direct Mark reveals this awareness only through occasional facial expressions. The more honest Kurt gives voice to it. Finally, he senses that physical contact may be the only way to reestablish a link to Mark. This culminates in a hot tub scene of unasked for massage. Mark at first is taken aback by this regression to adolescent playing around, but when Kurt tells him to "settle in," he does, becoming so astonishingly submissive he lets his defending hand sporting his wedding ring sink passively into the tub's water. Exactly what finally transpires here is left unclear, but what is not unclear is that nothing durable beyond the moment has taken place, that no bond of any sort has been reestablished between these guys. Their goodbyes are accordingly pretty emotion free and seem to come not a moment too soon. As a chronicle of time, change and loss, the film is undeniably affecting. If it has a flaw, I'd say it's a certain monotony arising from the focus on only two characters in an extremely closed situation. Given this narrowness, the film more resembles a lyric poem read aloud than a dramatic action, and, despite the beautiful photography, this makes for a very long 76 minutes indeed." A Walk in the Woods Chris Roberts | Astoria, NY | 02/07/2007 (3 out of 5 stars) "As kids we all have friends that as adults we no longer have anything in common with other than the past. And we have also all tried to bridge that gap between the then and the now, usually by reminiscing about shared alcoholic beverages, shared girlfriends, and shared memories. This melancholy film directed by Kelly Reichardt explores those feelings of lost friendship and the unrelenting nature of passing time. The simple tale involves two old friends, now on much different life paths, who decide to spend a weekend together in the woods. Reichardt directs "Old Joy" with a slow hand that has no interest in posing for you or winning over your approval. She also has no ace up her sleeve even though I, raised on "Brokeback Mountain" and "Twentynine Palms," was fully expecting something extraordinary out of this little trip of theirs. Rather the joy comes from the small things, as in life, such as Kurt (Will Oldham) musing about his overly adventurous trip to buy a notebook and the beautiful nature photography that will make you wonder if we weren't intended to live closer to nature. As their time together progresses the differences between them become all too apparent. Mark (Daniel London) has gone domestic on Kurt, and that is just the way it is. Of course he has been well paid for his belief in the system, his car is nicer, he actually has a cell phone, and his wife back home is carrying his child. But, as is always the case, he is tied to these properties that force him to lead a lifestyle that is not at all free. The wife doesn't want him to leave, the cell phone keeps ringing, and he gets very uncomfortable when Kurt starts smoking in his car. Based on his choice for driving entertainment (Air America) we are meant to believe that he is at least a self-proclaimed liberal, but standing next to Kurt he looks downright conservative. While he listens to the weighty matters of the day, such as the energy crisis, Kurt is out on the street giving his last dollar to a homeless man. Kurt's world is so small that he doesn't need to know about the energy crisis or Bush's double speak. He just needs to make it from day to day, and without all the modern trappings he is free to do that however he so chooses. Considering Reichardt's somewhat famous transient lifestyle it is easy to guess whose side she is on. That is not to say that Kurt is given an angelic portrait. His ramblings are long and straddle the fence between incoherent and BS, and he is stuck trying to pull off the look where he has more hair on his face than he does on his head. But despite his disappointment in Mark's decision to go domestic he never criticizes; he inquires and makes snarky comments to the waitress, but is always supportive of what he does with his life. I can't recommend this film however, because it just cuts a little too close to the banality of real life. Why not just go out into the woods and listen to your real friends babble nonsense after one too many beers? My childhood friends became Republicans, businessmen, and weirdoes, and those are just the ones I kept in touch with. What "Old Joy" does succeed at is reminding us that it is far too easy to become engulfed in the here and now, and that a little trip out of your comfort zone every now and then would probably do you a world of good. **3/4 " Old Joy John Farr | 07/23/2007 (5 out of 5 stars) "Mapping the psychic places where old friendships go to die, Reichardt's two-man (and one dog) road picture subverts the buddy drama with its slow, somber rhythm and air of unspoken longing. Kurt, a flaky, pot-smoking New Age type ably played by real-life musician Oldham, desperately wants communion with his more grounded friend Mark, who denies that anything is wrong, though his face and body language tell a different story. Reichardt's poetic evocation of their bucolic surroundings--birds, trees, woodlands--add to the tinge of unsettling melancholy. "Old Joy" might feel slow and plotless to some, but patient viewers will be rewarded by this film's subtle, near-wordless study of amicable alienation. It has the tang of truth." It's like.....a Rorshach test! S. J. Osburn | 06/17/2007 (5 out of 5 stars) "Reviews of this movie are alllll over the place. I've been amazed at the variety of interpretations I've read -- not just on Amazon.com but on metacritic and imdb. Takes on Kurt include: he's the real idealist; he's unable to give up his college-day lifestyle; he's a kind of street saint. Takes on Mark include: he's uptight; he's conceited (?); he doesn't really like Kurt any more; he's given up his idealism, and more. I could go on...but will only mention the variance in response to the radio program, Air America,that Mark keeps playing on the car radio. Reactions to that vary from calling it "Marxist invective" (LA Weekly) to calling Mark is a wannabe or fake liberal because he listens to it!

I finally decided that the non-obvious, not-spelled-out, low-dialogue qualities of this film allow people to project onto it whatever is on THEIR minds. That being said, here's what I thought -- and felt: The salient feature of this film is its hyper-realism. We are accustomed to Hollywood flicks in which the world is a kind of plastic-and-aluminum California or New York urban playground. In Old Joy, though, the world is seen largely from car windows (sometimes it's seen reflected from car windows) and consists of parking lots, rundown neighborhoods, grey skies, tacky restaurants, trucking firms with trailers outside them, and mud puddles. Then when you get to the mountains, the world consists of trees, moss, leaves, water and sky - but also, trash that people have thrown into the forest. I can't say enough to let you know how REAL this film looks and feels. You can almost smell the forest. As Mark is loading his car at his house, his neighbor is mowing the lawn, and the noise overwhelms your senses. Mark's wife is plain-looking and seems to be a -- well, a real woman. Mark himself has quite a schnoz on him (the reviewer who called it "aquiline" was being kind - it's a hatchet blade!) but is cute-ugly anyway. I suppose this is the place to say that the extremely different looks of the two main actors make one wonder whether the film should be subtitled "The Parable of the German-Scandinavian and the Jew" -- in which the German-Scandinavian succumbs to his hereditary tendency to depression while the American Jew gets on with practical life -- but if I say that, I'm liable to get zapped pretty badly by certain types, eh? Anyway. My read on the movie was that Mark is a good, mentally-healthy, idealistic person who loves his wife and is kind to his friends, even weird friends. Kurt is a strange-o who doesn't just smoke weed for fun, but has come to really NEED it, and may be in need of other substances as well; he's a loser, and may become a homeless loser before long. He isn't stupid nor evil, but he's directionless and hasn't made the right kinds of connections to make his life work. At one point in the movie Kurt begins grunting in a very bizarre manner which I have only heard from men who are mentally ill (I admit it, I'm a counselor). This is a great bit of acting, but I don't know how nor why other reviewers seem to be ignoring the facts about Kurt - he's a crazy drughead on the way down. To me much of the point of the movie is that a really good friend (Mark) can offer friendship even as an old friend sinks into total lost-ness, and the Lost Boy (Kurt) has friendship to offer as well. Am I alone in thinking that "Old Joy" is the joy of youth, which Mark manages to remember fondly while moving on, but Kurt tries, futilely, to recapture through chemicals and trips to the woods? Or hey....maybe this movie means something else altogether, such as: People who listen to "Marxist invective" on the radio are actually closet drug nuts themselves. Nope, I don't think that's what it means!" |