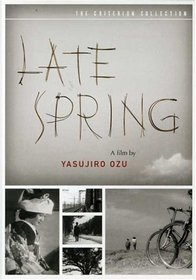

| Actors: Chishu Ryu, Werner Herzog, Yuuharu Atsuta, Chris Marker, Setsuko Hara Directors: Wim Wenders, Yasujiro Ozu Creators: Wim Wenders, Yasujiro Ozu, Chris Sievernich, Kazuo Hirotsu, Kôgo Noda Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama Sub-Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama, Family Life Studio: Criterion Format: DVD - Black and White,Full Screen - Subtitled DVD Release Date: 05/09/2006 Original Release Date: 01/01/1949 Theatrical Release Date: 01/01/1949 Release Year: 2006 Run Time: 1hr 48min Screens: Black and White,Full Screen Number of Discs: 2 SwapaDVD Credits: 2 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 17 Edition: Criterion Collection MPAA Rating: Unrated Languages: English, German, Japanese Subtitles: English |

Search - Late Spring - Criterion Collection on DVD

| Late Spring - Criterion Collection Actors: Chishu Ryu, Werner Herzog, Yuuharu Atsuta, Chris Marker, Setsuko Hara Directors: Wim Wenders, Yasujiro Ozu Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama UR 2006 1hr 48min The first of a series of intimate family portraits that would cement Yasujiro Ozu?s reputation as one of the most important directors in cinema history, Late Spring tells the story of a widowed father who feels compelled t... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

Similarly Requested DVDs

|

Movie ReviewsFather and Daughter James Paris | Los Angeles, CA USA | 07/12/2000 (5 out of 5 stars) "This is one of a handful of films I consider one of the most moving ever made. Director Yasujiro Ozu has created a symphony of the emotions regarding the relationship between a father (played by Chishu Ryu) and his daughter (the great Setsuko Hara). There is a Zen-like quality to this and Ozu's other great films -- including TOKYO STORY (1953). At salient points in the action, the camera leaves the characters and focuses upon the middle distance, with sad orchestral music welling up. I am told that this technique is an example of "mono no aware," or sympathetic sadness. Ozu does not hammer at the viewer: He knows when to pull back and let the feelings take root and start to spiral up your spine. It is an instinctive talent that few filmmakers have. Ozu almost NEVER moves his camera, which he sets up on a short tripod about 3 feet high -- just about the height of your head if you were sitting on a tatami mat and interacting with the characters. I saw a recent documentary about Ozu in which almost everyone who ever worked with this quiet genius broke into tears. The last shot was simply of his funeral monument, with the same sad music welling up. Ozu was one of a kind. We shall not look upon his like again." How many masterpieces can an artist have? anthemic | Australia | 07/01/2000 (5 out of 5 stars) "In my review of 'I Was Born But...' I brought attention to one of Ozu's subject matter motifs - estranged relationships between children and parents. Usually when the children are not kids - as in 'Late Spring' then Ozu develops this motif with the topic of marriage. In this case, the widowed father in realising his selfishness to 'keep' his daughter urges her to marry before its too late. This sudden parental wish is not without resistance from his daughter. The fact that this film is 'post-war Ozu' provides an important contextual backdrop - that is, Japan's fascination for things American. Moreover, it is the idea of marrying for love than for traditional duty. With much parallel action at work, the narrative is consumed with trying to match Noriko with suitors. At the same time, marriage becomes conceptually compared with other characters in terms of divorce and tradition. Again, spatial violation and mimimalistic camera shots are prevalent. Furthermore, Ozu's sense of graphic composition is superb here as each shot - be it an object or room - looks strikingly articulated. I don't want to spoil the final scene - however I will say that it is one of the finest moments in the history of cinema.See this film and you will love the father, as you will the daughter, and even the interfering Aunt. Its not just Ozu's excellent sense of humanism but his ability to share the emotional resonance of his characters with the viewer. Wait for that final scene and be spellbound! Ironically, if it hadn't been for Ozu's estranged relationship with his father - he might never had so much tenderness to convey in his films." Poignant study of character anthemic | 06/24/2002 (5 out of 5 stars) "Many of Ozu's films are variations on a theme, namely, parents pressuring a daughter to marry and the impact the marriage ritual has on the family. Late Spring is the first and probably finest example of this theme. In the old Japan, marriage was not an option, it was a given. But after World War Two, Japanese women became more independent in their thinking. They didn't always get their way, but they began to challenge the old ways. We can see this in Late Spring. Noriko is sweet but at the same time stubborn. She doesn't want to get married. During a trip to Kyoto, she gently pleads with her widowed father to let her stay with him. It's a touching scene that will tug at your heart.But Late Spring is more than a movie about social change. It's a poignant study of character. The beauty of Ozu's movies is that you get to know everyone so well, as if they were members of your own family. We can understand why Noriko is content to live with her father. But we can also sympathize with her Dad who worries she will become an old maid. The ending of this movie has a beautiful sadness to it. It is one of the most moving films I've had the privilege of watching." Father-Daughter Bond Scrutinized with Ozu's Masterful Resona Ed Uyeshima | San Francisco, CA USA | 07/01/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "**The original review is for the all-region DVD version previously available in Asia only. Updated comments for the two-disc Criterion Collection DVD set released on May 9, 2006 are included below.**

Through an eBay auction, I was so lucky to find a DVD of Yasujiro Ozu's "Banshun (Late Spring)" since it's not available yet in the US, where I imagine it will be released some day through the Criterion Collection. This is how new viewers like myself have discovered the other two classic films of his Noriko trilogy, 1951's "Bakushu (Early Summer)" and 1953's "Tokyo Monogatari (Tokyo Story)". This 1949 film is perhaps the most Japanese of the three as it concerns the rather unearthly devotion a daughter named Noriko has for her widowed professor father, Shukichi. While an American film would have touched upon the incest angle, under Ozu's immaculate direction, there is nothing unseemly about the relationship. She thoroughly enjoys taking care of him, but her father knows she must get married. A meddlesome aunt named Masa aggressively sets up an arranged marriage with a supposed Gary Cooper-look-alike (though we never see him). Noriko resists all efforts until Shukichi and Masa convince her that he is getting married to a woman she eyes with remorse at a Noh play. Noriko reluctantly agrees to marry but never really accepts the reasoning that she needs a husband. In a beautifully economic scene only Ozu could convey, Shukichi peels an apple after the wedding and sadly bows his head to cry. Even though the later "Tokyo Story" deals with death, this is the most emotionally naked of the trilogy, as it is palpable how Noriko cannot truly succumb to the supposed joy of marriage. It's no wonder Setsuko Hara became a huge star in Japan with this film. She plays Noriko with a wellspring of emotion from scene to scene - headstrong, petulant, flirtatious (the sliced pickle comment is pretty saucy), blindly devoted, masochistic, and guardedly happy. Ozu gives her the full glamour treatment as well, having the camera linger in a medium shot on her beautiful, often smiling face, for instance, during the fanciful bike ride on the beach and the lengthy Noh play scene. Even though Hara plays three different characters in the trilogy, all named Noriko, it's fascinating to see how she seamlessly manages the evolution from high-spirited daughter here to emancipated working woman choosing to marry on her terms in "Early Summer" to resigned widow lost in her solitude in "Tokyo Story". She is memorable. Familiar Ozu regular Chishu Ryu gives his most sympathetic and accessible performance as Shukichi with a touch of appropriate absent-mindedness. The rapport between the two feels genuine, and it amazes me how they can be so convincing as father-daughter in one film and brother-sister in the next. Another Ozu mainstay, Haruko Sugimura, excels at willful, often irritating characters, and her unrelenting portrayal of Masa exemplifies her unique talent. It's intriguing that Hara and Sugimura have an almost duplicate scene in both "Late Spring" and "Early Summer" where the older woman cajoles Noriko to marry - the actors play the scene with sweetness and surprise in the latter film, whereas turmoil and regret fill a similar turning point in this one. There is some wonderful acting on the sidelines - the comically cherubic Masao Mishima as the "unclean" Mr. Onodera (I love the scene where he keeps pointing in the wrong direction to get his bearings in Kamakura); Jun Usami as Shukichi's assistant Hattori, a seemingly perfect suitor for Noriko who turns out to be unavailable but not overly so; and Yumeji Tsukioka as Noriko's worldly divorced best friend Aya. Note Aya's completely Western home (ironically filmed at Ozu's typical tatami-sitting eye level), one of many interesting American touches in the film, including the anachronistic use of "Here Comes the Bride" to introduce the wedding scene. The Kyoto sequence is particularly affecting with a fine use of real locations (Kiyomizu Temple, Imperial Palace) and the moving scene when Noriko and Shukichi come to their mutual understanding of the future. This is said to be Ozu's personal favorite, and I can understand why as the director tells a simple story with relatable truths and honest intensity, even though the relationship is rather unusual by Western traditions. A holistic view of the Noriko trilogy shows "Early Summer" to be more comical and "Tokyo Story" more universally poignant, but "Late Spring" is a gem all on its own. This DVD gratefully has English subtitles, though the translation can be a bit sketchy at times. The print transfer is not pristine (some scenes are overly dark) but not as bad as I feared. There are no extras, as I expect there will be once Criterion does decide to release this classic. **ADDENDUM FOR THE CRITERION COLLECTION DVD RELEASED ON MAY 9, 2006 (updated on 5/16/2006)** As I had been anticipating, the Criterion Collection has finally completed Ozu's Noriko trilogy with the release of this wondrous masterpiece on a two-disc DVD set. The print is marginally improved over the Asia-originated, all-region DVD in circulation for several years, but the subtitles make far more sense in this edition, which now includes the meaningful lyrics to the Noh play at the center of the movie. However, the major asset is the informative commentary from Richard Pena, program director of New York's Film Society at Lincoln Center. He speaks in depth about the themes of the film and Ozu's broader career, though sometimes his comments inappropriately precede the action on the screen. Most importantly, Pena provides the much-needed historical context to the story, in particular, the implied impact of WWII labor camps, which led to the nearly intractable relationship between father and daughter. The second disc has Wim Wenders' excellent 1985 documentary, "Tokyo-Ga", which shows the director retracing Ozu's steps in a modern-day and almost completely unrecognizable Japan. A great buy." |