| Actors: Francesca Annis, Daniel Craig, Stephen Rea Director: Howard Davies Creators: Ian Wilson, Howard Davies, Kevin Lester, Bettina Bennewitz, Eamon Fitzpatrick, Gordon Ronald, Karen Robinson Hunte, Mary Mazur, Megan Callaway, Richard Fell, Simon Curtis, Michael Frayn Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama, Special Interests, Television, Musicals & Performing Arts, Military & War Sub-Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama, Special Interests, Television, Musicals & Performing Arts, Military & War Studio: Image Entertainment Format: DVD - Color,Widescreen,Letterboxed - Closed-captioned DVD Release Date: 05/13/2003 Original Release Date: 01/01/2002 Theatrical Release Date: 01/01/2002 Release Year: 2003 Run Time: 1hr 30min Screens: Color,Widescreen,Letterboxed Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 6 MPAA Rating: NR (Not Rated) Languages: English |

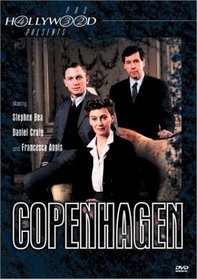

Search - Copenhagen (PBS Hollywood Presents) on DVD

| Copenhagen PBS Hollywood Presents Actors: Francesca Annis, Daniel Craig, Stephen Rea Director: Howard Davies Genres: Indie & Art House, Drama, Special Interests, Television, Musicals & Performing Arts, Military & War NR 2003 1hr 30min Inspired by actual events which have baffled and intrigued historians for years, this Tony Award-winning drama by Michael Frayn (Spies, Noises Off) comes to life in this stirring presentation. At a 1941 meeting, two bril... more » |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar MoviesSimilarly Requested DVDs

|

Movie ReviewsBrilliant, moving, cathartic Dennis Littrell | SoCal | 02/02/2004 (5 out of 5 stars) "Most viewers of this extraordinary play believe that it doesn't answer the question of why Werner Heisenberg came to Copenhagen in 1941 to visit his mentor Niels Bohr. And this is true: playwright Michael Frayn does not give a definitive answer to that intriguing question. But he does give an interpretation.We must go to the "final draft" of their recapitulation of what happened--the "their" being the three of them, Heisenberg, Bohr and his wife Margrethe, who appear as ghosts of themselves in the now empty Bohr residence. In the scene that didn't happen, instead of walking away from Heisenberg in the woods, Bohr contains his anger and confronts his one-time protege. He tells Heisenberg to do the calculation to determine how much fissionable material would be necessary to sustain a chain reaction.Heisenberg had believed without doing the calculation that the amount was somewhere in the range of a metric ton. As he does the calculation in his head he realizes that the amount would be much, much less, only 50 kilos. This changes everything because it made the bomb entirely possible. Frayn's point is that it is far better that Bohr did not tell Heisenberg to do the calculation because if he had, it is possible that Nazi Germany would have developed an atomic bomb under Heisenberg's direction. But this does not answer the question of why Heisenberg came to Copenhagen. Margrethe has her own answer: he came to show himself off. The little man who is now the reigning theoretical physicist in Germany had come to stand tall and to let Bohr, who was half Jewish, know that he had the ability to save him from the Nazis.This is the "psychological" answer and it plays very well. Heisenberg, like most Germans felt humiliated by the defeat in the Great War and had suffered severely in the economic deprivations that followed. And like most Germans Heisenberg, who was not a Nazi, compromised his principles by acquiescing in Nazi rule because he believed that it would return Germany to "its rightful place" as an economic and military leader in the world. He came to Copenhagen in 1941 in triumph. His triumph, understandably, was not well received.The more blunt question of did Heisenberg expect to find out whether the Americans were making a bomb or to get Bohr to help with the German project is also answered in a psychological way. The answer is no, because he knew that Bohr would not help him even if he could. As it turns out at the time Bohr had no knowledge of what the Allies were doing. The other question, a question that would haunt Heisenberg for the rest of his life, was did he delay the German bomb project in order to prevent the Nazis from acquiring the bomb--as he claimed--or was the fact that they were not able to develop a bomb just a matter of not having the ability? To this question playwright Frayn's answer is that Heisenberg would have developed the bomb if he had been able. This answer is the generally accepted one based on the historical evidence, part of which comes from some careless words from Heisenberg himself that were recorded by British intelligence after Heisenberg was captured and sent to England. What Frayn does so very well in his brilliant play is show us that Heisenberg's need to succeed and his need to feel national pride would not allow him to behave otherwise.The direction of this PBS production by Howard Davies relies heavily on an interesting device. Bohr's wife becomes an objectifying factor who is able to step back from the emotional situation and to see both men clearly and to guide the audience toward an understanding of their relationship. Over the years, she and Niels Bohr served as surrogate parents to Heisenberg. He was the little boy who came home to his parents in 1941 to say, Look at me. I am a great success. Only problem was his "success" could not be separated from the Nazi occupation of their country, and Heisenberg was too obtuse and insensitive to see that.In truth, Heisenberg was not entirely aware of his own motivation. He did not know why he came to Copenhagen. Neither did Bohr. But Margrathe did. An accompanying point to this idea is the story of Bohr bluffing Heisenberg and others during a poker game some years before. It appeared from the fall of the cards that it was extremely unlikely that Bohr had made a straight that would win the pot, and yet he kept on betting until all the others threw in, and then when he showed his hand, he had no straight. He had fooled himself. Frayn's position is that in believing he had come to Copenhagen for innocent reasons, Heisenberg was unconsciously fooling himself. Furthermore the fact that he had not done the calculation was equivalent to Bohr's not looking back at his hole cards to see what he really had.This is not an easy play. I have seen it twice and benefitted from the second viewing. It is not, however, a play only accessible to intellectuals. The ideas are presented in a clear manner so that any reasonably intelligent person can understand them. Frayn employs an elaborate metaphor involving Heisenberg's famous uncertainty principle to elucidate the relationship between Bohr and Heisenberg. They are particles that will collide: Heisenberg the elusive electron, neither here nor there, the very essence of uncertainty, Bohr the stolid neutron. Davies has the two circling and circling one another, even chasing one another, as in a dance while Margrathe watches.I found the play brilliant, moving, and ultimately cathartic as all great plays should be. Davies' direction and the sense of time and place greatly facilitated my enjoyment. And the acting by the three players, Stephen Rea (Bohr), Daniel Craig, and in particular, Francesca Annis, was outstanding." NOW I get it! Valerie A. Lord | Malta, NY United States | 09/30/2003 (5 out of 5 stars) "I was fortunate to see this play during it's Broadway run. While it was brilliantly acted, directed and was able to add one chilling element the film can't (the onstage audience in the elevated gallery, always looking like a silent jury)at times I had trouble following when we were seeing a flashback, an inner dialogue, or plot development. (The physics in the play is quite well presented but trust me, don't have that second tequilla shot before the curtain, no matter what!You really have to be on the ball for this one.) However, now having seen the film twice, many things come clear. The magic of film allows the players to think private thoughts without us mistaking them for side comments being made under the breath. Also, it is very clear when we are listening to the ghosts and the live players. But what REALLY gave me an ah-ha moment was when I finally saw that the play is crafted to mimic the act of nuclear fission. Instead of a neutron colliding with and splitting an atom into several directions, setting off a chain reaction, we witness two brilliant physicists colliding, also under forced circumstances and the split is represented by the various possible outcomes of that collision. We view several versions of the same encounter, each with different implications and motives. I can't wait to see this again and see where bells "ding" for me this time. The score is haunting and adds a great deal, as solo piano is unsurpassed in evoking a sense of isolation and loneliness. Acting is uniformly solid. I know I'll get lambasted for this, but I really preferred this cast over the b'way cast, especially Steven Rea, who added just a touch of melancholy to the role that I don't remember in the original. Give it a try. You may come away with the uneasy feeling that in a roundabout way, these men may have saved our planet." Very VERY Bohring D. Roberts | Battle Creek, Michigan United States | 10/13/2003 (5 out of 5 stars) "In 1941, after having their friendship interrupted by World War II, Werner Heisenberg set off to Denmark to visit with his old friend & mentor, Niels Bohr. What, precisely, took place at this rendezvous has been debated for over 60 years by scientists, philosophers of science, historians of science & even laymen.The present film is a re-enactment of this meeting, based on the play written by Michael Frayn. Much of the discussions could have possibly taken place, in some form or other. Of course, only Bohr and Heisenberg could say for sure. Alas, both are long since deceased.At stake in the story is the $60,000 question: was Heisenberg in Copenhagen to coerce Bohr to help the Nazis with the development of the atomic bomb? Was he there to entice his old friend to solicit information on the American efforts (Manhattan project)? Were his overtures MISUNDERSTOOD by Bohr, compelling the latter to mis-construe any of the above? Or, did Heisenberg simply visit his colleague in hopes of challenging him to a game of tiddly-winks?This story will not provide the answer, but it will certainly offer new avenues to ask the questions in the appropriate context. The film often references Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle and is told in a rather Twilight-Zone-esque fashion. A nice twist is the fact that the storyline makes a nexus of the everyday-world with the abstract realm of theoretical physics.Almost as important as the subject matter of the film is the acting. There are only 3 characters in the storyline: Heisenberg, Bohr and Bohr's common sense-laden wife. The acting thus takes on extra-importance, and all three actors come thru brilliantly.The Cambridge physicist John Gribbin once wrote that "In the quantum world what you see is what you get and nothing is real. All you can possibly hope for are a set of delusions that agree with each other." Maybe, just maybe, this statement applies to interpersonal relationships as well." Not for science junkies only ophelia99 | USA | 01/16/2005 (5 out of 5 stars) "Although it does help to have a little background -- in my case college level physics and chemistry -- the play does such a brilliant job of getting across the little bit of physics one needs to understand what the characters are talking about that the film can be enjoyed by a total humanities person. (I watched this with someone with no significant science background, and she had no trouble following it.) What is really gripping here is the human drama, wonderfully written and acted, and the final, chilling revision of the past the ghosts try as a thought experiment."

|