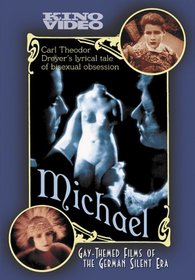

| Actors: Walter Slezak, Max Auzinger, Nora Gregor, Robert Garrison, Benjamin Christensen Director: Carl Theodor Dreyer Creators: Karl Freund, Rudolph Maté, Carl Theodor Dreyer, Erich Pommer, Herman Bang, Thea von Harbou Genres: Indie & Art House, Classics, Drama Sub-Genres: Indie & Art House, Silent Films, Love & Romance Studio: Kino Video Format: DVD - Black and White,Full Screen - Closed-captioned,Subtitled DVD Release Date: 12/14/2004 Release Year: 2004 Run Time: 1hr 33min Screens: Black and White,Full Screen Number of Discs: 1 SwapaDVD Credits: 1 Total Copies: 0 Members Wishing: 6 MPAA Rating: NR (Not Rated) Subtitles: English |

Search - Carl Theodor Dreyer's Michael on DVD

| Carl Theodor Dreyer's Michael Actors: Walter Slezak, Max Auzinger, Nora Gregor, Robert Garrison, Benjamin Christensen Director: Carl Theodor Dreyer Genres: Indie & Art House, Classics, Drama NR 2004 1hr 33min Studio: Kino International Release Date: 12/14/2004 Run time: 86 minutes |

Larger Image |

Movie DetailsSimilar Movies

Similarly Requested DVDs

|

Movie ReviewsLong forgotten silent masterpiece comes to life anonymous | United States | 11/07/2004 (5 out of 5 stars) "A master painter and his protege live in splendor, face relational conflicts, separation, tragedy, yet there doesn't seem to be a melodramtic note in the entire film. The acting is magnificent, and superior to many silent films. I was thoroughly suprised by the level of quality and sophistication of this movie. I can't label it as a gay film, although there are enough implications to justify those who have considered it thus. However, if you enjoy great silent movies, this one is a must see. You will be astonished. The commentary by the Danish scholar is insightful. Thoroughly enjoyable. And not an ounce boring. A truly excellent film and a genuine masterpiece of the Weimar cinema." Let the boy go Steven Hellerstedt | 11/27/2005 (4 out of 5 stars) "Brooding depression sets in when a famous artist's ward, and principal model, leaves him for a beautiful and much younger Russian princess. A young and not-yet-corpulent Walter Slezak plays the young model, and the title character, in Carl Theodor Dreyer's MICHAEL. Slezak, who's most famous as the duplicitous German sailor washed aboard Alfred Hitchcock's `Lifeboat,' is about the only recognizable actor in this 1924, German-produced, silent movie. Although Slezak is the featured star, the leading character is Benjamin Christensen's Claude Zoret, the great artist, usually referred to by the others simply as The Master. The story begins, and spends most of its time in, the Master's mansion - one of those big, drafty, rococo/Victorian art mausoleums that looks like a toney funeral home and, to that extent, more or less fits the movie. Young Michael is feckless and self-centered, good-looking enough to step comfortably in and out of an Arrow shirt ad, and its his image that graces the Master's greatest painting, `The Victor.' Disruption arrives in the form of Princess Lucia Zamikoff (Nora Gergor,) who persuades the initially reluctant Master to paint her portrait. Before the paint is dry Michael is in love with her, and ready to leave the Master. `Mikaël' was written by Danish Impressionist novelist Herman Bang (1857-1912.) (...). Danish film historian Casper Tyberg tell us, in his interesting and fact-filled commentary, that MICHAEL has a disputed place in the history of gay cinema. The movie's central relationship, between the Master and Michael, is at best ambiguous. There are, as Tyberg says, hints and `cues' of something more, but on screen there's only evidence of the Master's paternal affection, rather than passionate physical attraction. If, as Tyberg tells us, the theme was buried in the book, it is so in the film as well. Beyond the `cue' hunting MICHAEL is interesting if viewed as a giant step toward Dreyer's towering masterpiece of 1928, `The Passion of Joan of Arc.' Tyborg tells us MICHAEL was a `lost' film until a print was discovered in 1952. It wasn't released to many foreign markets during its original run. Even France wouldn't take it. A studio exec, if I remember Tyborg's comment correctly, said it was too boring even for the art houses. Probably so. Dreyer's movies tend to be character driven. This is the fourth one of his I've seen and I'm getting used to his heavy reliance on facial expressions and significant glances. However, unless the subject fits the method - as it does brilliantly in his `The Passion...' it gets to be pretty heavy going. Perhaps most difficult is the choice of an older, somewhat autocratic character as the one we're supposed to feel the most for. Christensen is perfectly fine as the Master, but Mary Pickford or Lillian Gish he ain't. It's hard enough to warm up to him, much less ache for the betrayal he suffers. So, a weak four stars for the watchably restored MICHAEL, a reserved classic that perhaps offers more to the historically curious than those who want to get emotionally caught up in a movie. " A fine example of "film as art" Barbara (Burkowsky) Underwood | Manly, NSW Australia | 05/27/2006 (5 out of 5 stars) "This 1924 German UFA production is perhaps one of Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer's most overlooked and almost forgotten films, but seen from the perspective of artistic quality and character psychology "Michael" stands the test of time. Dreyer's style of intimate character portrayals, meticulous and slow studies of faces, expressions and characters' emotions are all brought to the fore in this somewhat controversial film about a middle-aged artist and his young protégé. Although billed as one of three `Gay-themed films of the German Silent Era', there are no overt references or gestures implying a gay relationship, and at times the relationships and feelings of the characters remain somewhat ambiguous and perhaps open to viewer interpretation, but deliberately so. To me, "Michael" seems first and foremost to be a study of characters, their emotions, and their relationships with each other. The scenes are mostly set in the Master painter's house which is filled with lavish and elaborate turn-of-the-century furniture and decorations which greatly assist in creating a certain atmosphere and the backdrop to the characters' interactions with each other. To enhance the character study, lighting is used very effectively, as are various close-ups, which was not yet commonplace in the mid 1920s as they are today.

"Michael" closely follows the novel by the same name, written by gay author, Herman Bang, who no doubt was able to embellish the relationship between Master and protégé very effectively, making the whole film a bitter-sweet study of human feelings and relationships, and lifting it to the heights of artistry. Not one, but two love-triangles feature in this story, one being a sub-plot to parallel the main relationship between the Master and Michael, the latter falling in love with a beautiful countess who sits for a portrait. Not only is classical art a main theme in the film, but Dreyer strove to make "Michael" a work of art in itself, and judging by European reviews at the time, it succeeded very well. This film appealed to the high-brow and aristocratic societies of the 1920s, but for the serious viewer of silent and/or art films, "Michael" should still have as much appeal as it did in its day. As a bonus feature, an audio commentary by a competent Danish Film scholar provides further insight into the techniques used by Dreyer and other interesting background information on the players. The picture quality is very good throughout, and the gentle classic music accompaniment fits the mood and images perfectly. All round, a high standard production with emphasis on visually stunning sets and human relationships. " |